article

America: Boom, Bust, and Baseball Guide: The Revolution’s Number One Boy

JAN 27, 2010

In 1935, Clifford Odets began a new era in American drama.

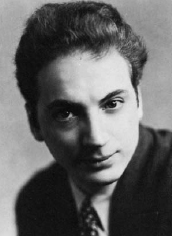

In 1935, Clifford Odets began a new era in American drama. With three plays running simultaneously on Broadway – Waiting for Lefty, Awake and Sing!, and Until the Day I Die – Odets dazzled New York with his innovative language, pushing aside the heroes of 1920s sentimental theater to make room for his down-andouters. Depicting the destitute, Odets transformed the despair of the Depression into a lyrical realism new to the American stage.

Odets’s career is bound up with the rise of the Group Theatre. In 1931, the Group Theatre burst onto the boards of New York, bringing a new style of acting to the American stage. Inspired by Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre, the Group emphasized ensemble work, rehearsing for months to create performances in which character, text, and theme interacted not as autonomous pieces, but as an intertwined, cohesive unit. Their detailed examinations of character and tightly knit ensemble elevated the craft of American acting.

With a new style of acting, a new playwright was needed. Under the influence of the Group Theatre, Odets found his voice. Odets had joined the Group as an actor, playing bit parts. Enraptured by the energy of the company, he began to write plays without starring roles. Instead, he penned six to eight equal parts, creating a gallery of characters to display the chemistry of the ensemble. Odets became the playwright-in-residence of the Group, scripting their most famous productions – Awake and Sing! (1935), Paradise Lost (1935), and Golden Boy (1937). But the play that launched him screaming into the world was Waiting for Lefty (1935). Written in three days and directed by Odets, Waiting for Lefty premiered on January 5, 1935. Depicting a group of cabbies on the brink of strike, Lefty’s raw dialogue captured the anger of America: “The cards is stacked for all of us. The money man dealing himself a hot royal flush. Then giving you and me a phony hand like a pair of tens or something.” On opening night, theater critic Harold Clurman wrote, the audience leapt to their feet, crying “STRIKE! STRIKE!,” and surged to the stage in “a kind of joyous fervor….[O]ur youth had found its voice.”

With a new style of acting, a new playwright was needed. Under the influence of the Group Theatre, Odets found his voice. Odets had joined the Group as an actor, playing bit parts. Enraptured by the energy of the company, he began to write plays without starring roles. Instead, he penned six to eight equal parts, creating a gallery of characters to display the chemistry of the ensemble. Odets became the playwright-in-residence of the Group, scripting their most famous productions – Awake and Sing! (1935), Paradise Lost (1935), and Golden Boy (1937). But the play that launched him screaming into the world was Waiting for Lefty (1935). Written in three days and directed by Odets, Waiting for Lefty premiered on January 5, 1935. Depicting a group of cabbies on the brink of strike, Lefty’s raw dialogue captured the anger of America: “The cards is stacked for all of us. The money man dealing himself a hot royal flush. Then giving you and me a phony hand like a pair of tens or something.” On opening night, theater critic Harold Clurman wrote, the audience leapt to their feet, crying “STRIKE! STRIKE!,” and surged to the stage in “a kind of joyous fervor….[O]ur youth had found its voice.”

Audiences saw their lives reflected in Odets’s characters and language – language the critic Alfred Kazin described as “boiling over and explosive….Everybody on that stage was furious…the words, always real but never flat, brilliantly authentic like no other theater speech on Broadway.” Odets spoke the language of revolt-the fight against a “life printed on dollar bills.” He showed hope and despair, promise and pain.

As his style developed, Odets moved from the newspaper-like reporting of Waiting for Lefty to a more nuanced portrayal of the middle class in Paradise Lost. In what he called his favorite play, the hero was not an individual struggling against a known enemy, but “the entire American middle class” struggling against a “life nullified by circumstances” and “false values.” The Depression stretched on, banging on the doors of middle-class families like the Gordons in Paradise Lost. Odets presents the chasm between aspiration and reality, between what they hope for from the American dream and what they get, in Leo Gordon, who gives his workers a raise even as he’s poised for bankruptcy; in Pearl, who practices Beethoven sonatas for the concert she will never give; and in Ben, whose athletic prowess leads nowhere.

After Paradise Lost, Odets began writing films for Hollywood such as The General Died at Dawn, Humoresque, and The Sweet Smell of Success, as well as film adaptations of his plays. Though he wrote continuously for the screen, he did so with a sense of unease. Concerning Hollywood producers, he told Time, “They want to emasculate me.” Harold Clurman notes,

“For Odets…Hollywood was Sin.” Not surprisingly, then, he returned to the stage several times to write Golden Boy (1937); Clash by Night (1941); The Country Girl (1950); The Flowering Peach (1954); and The Big Knife (1949), a semi-autobiographical story of a Hollywood sellout.

Though his subject often changed, the one constant in Odets’s oeuvre was his innovative use of language. Unrefined yet poetic, his dialogue, according to Clurman, “is ungrammatical jargon-and constantly lyric. It is composed of words heard on the street, in drugstores, bars, sports arenas, and rough restaurants….[I]t is the speech of New York.” Odets’s blend of non sequitur and symbolism, irony and wisecrack gave rise to the term “Odetsian line,” a sad, funny idiom: “What this country needs is a good five-cent earthquake” (Awake and Sing!) or “I’m in you like a tapeworm” (Paradise Lost).

The young Odets wanted to be a composer and musical structure shapes his writing. “Each of my plays,” he said, “I could call a song cycle on a given theme.” Arthur Miller went further, declaring “Odets was turning dialogue into his personal jazz…it was a poet’s invented diction, with slashes of imagery of a sort never heard before, onstage or off.”

This linguistic jazz changed American stage language, influencing writers like Miller, Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee, Sam Shepard, David Rabe, and David Mamet. Only a short distance lies between the Yiddish inflected speech of Odets’s families, Miller’s Lomans, and Mamet’s bedeviled salesmen. Williams once claimed, “I am very much an Odets character-male, poor, and desperate, American, and yet amazingly positive.” And in Odets’s fast-talk-“Cut your throat, sweetheart. Save time.”-one can see the beginnings of Mamet’s elliptical staccato. The riotous legacy of Clifford Odets is alive and kicking.